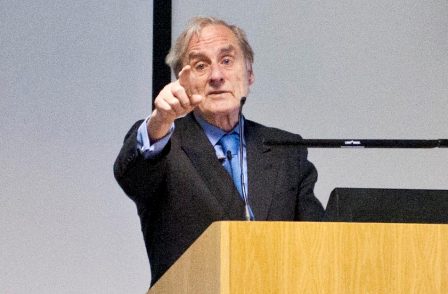

A new guide to better writing produced by editor extraordinaire Sir Harold Evans should be required reading for all journalists, writes Dominic Ponsford.

Do I Make Myself Clear is packed with gems culled from his 70-plus years as a wordsmith. It is a virtual boot camp for writers which should help them produce prose which is lean, direct, clear and engaging.

Here are six tips Press Gazette has selected from the book, reproduced with kind permission of the author:

-

Get moving

We’ve seen how even writers of renown try to squeeze in more words than the structure can accommodate. That confusion advertises itself.

More insidious is the passive voice that so often sneaks past usage sentries. It robs sentences of energy, adds unnecessary words, seeds a slew of wretched participles and prepositions, and leaves questions unanswered:

It was decided to eliminate the coffee break. Which wretch decided that?

Vigorous, clear, and concise writing demands sentences with muscle, strong active verbs cast in the active voice.

Active voice:

The pope kissed a baby on the forehead, leading the crowd of thousands to erupt in cheers and praise. (19 words)

Passive voice:

A baby was kissed on the forehead by the pope, leading the crowd of thousands to erupt in cheers and praise. (21 words)

When you write in the passive voice you can’t escape adding fat any more than you can escape piling on adipose tissue when you grab a doughnut.

Doughnut:

The Great Wall of China has been walked by millions of people. (12 words)

Active:

Millions of people have walked the Great Wall of China.

(10 words)

Doughnut:

There were riots in several cities last night in which several shops were burned.

Active:

Rioters burned shops in several cities last night.

The passive voice is preferable if not inescapable in four categories:

(i) When the doer of the action is not known:

The lease was sent back to us without a signature.

(ii) When the receiver of the action merits more prominence than the doer:

A rhinoceros ran over Donald Trump today.

That is active (and news). But there is a case for believing that more people are interested in Mr. Trump than a bad- tempered rhino:

Donald Trump was run over by a rhinoceros today.

(iv) When the length of the subject delays the entry of a verb:

The complexity of designing an aerial propeller when none had ever existed, marine propellers having simply to displace water and not cope with the complex aerodynamics of flight, troubled Wilbur.

Better:

The complexity of designing an aerial propeller was troubling to Wilbur since none had ever existed, and marine propellers had simply to displace water and not cope with the complex aerodynamics of flight.

-

Be specific

All great writing focuses on the significant details of human life and in simple, concrete terms. You cannot make yourself clear with a vocabulary steeped in vagueness. Comb through passages you are writing or editing on the alert for strings of overworked abstract nouns:

amenities, activities, operation, purpose, condition, case, character, facilities, circumstances, nature, disposition, proposition, purposes, situation, description, issue, indication, regard, reference, respect, connection, instance, eventuality, neighborhood, satisfaction.

Words like these squeeze the life out of sentences.

Chase out most abstract words in favor of specific words. Sentences should be full of bricks, beds, houses, cars, cows, men, and women.

On TripAdvisor.com, an online travel guide, I read:

“Mombasa is well known among travelers as a place to buy traditional Kenyan crafts and clothing. The city is full of markets that have been operating in the same way that they do today for hundreds of years. These markets are attractions in themselves, as well as places to shop, as they give visitors a genuine taste of Mombasa.”

Fair enough, but the market for specifics thrives when you go shopping with Martha Gellhorn, who arrived in Mombasa to set up house in 1964:

“We shopped ourselves blind. It is never heart-lifting to concentrate on garbage cans, pillow slips, knives, forks etc. But there were compensations. Between the bath-towel store and the frying-pan emporium, one passed on the Mombasa streets a whole exotic world. Sikhs with their beards in hair nets, Indian ladies wearing saris, caste marks and octagonal glasses. Muslim African women, enormous and coy, hidden except for their eyes in black rayon sheets, tattooed tribesmen loading vegetable trucks; memsahibs driving neat cars filled with roceries and blond children; bwanas in white shirts and shorts and long white socks, hurrying to their offices. . . . Bicycles zoomed in like flies.”

-

Ration adjectives, raze adverbs

In World War II Britain, posters interrogated travelers waiting for a train: Is Your Journey Really Necessary? Subject your sentences to the third degree: Is your adjective really, really necessary to define the subject of your sentence, or is it there for show? What exactly, precisely, does your adverb add to the potency of this or that verb or adjective?

You can see we are in trouble already. Really, exactly, and precisely have elbowed in. Adverbs modifying verbs and nouns and adjectives have the excuse that they tell us where,when, and how, but mostly they clutter sentences.

Get rid of adverbs hitching a ride on verbs whether quickly, slowly, lazily, feebly, or wearily. Most ly adverbs don’t enhance. They enfeeble. If you are inclined, judgmentally, to challenge this assertion, I will ask Stephen King to terrify you with his story of dandelions growing sinisterly in a lawn.

The author of the sentence “I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs” feels strongly. Alternatively, you could use the Adverb Annihilator free on any laptop or mobile. Just type in ly and interrogate all the ly adverbs that pop up.

Adjectives are more seductive. As a young reporter assigned to cover a few soccer matches, I was checked in admiring my colorful writing by a stylebook chastisement: “Genesis does not begin ‘The amazingly dramatic story of how God made the world in the remarkably short time of six days.’” The best of the good sportswriters today have lean prose and narrative excitement…

And beware of superlatives. Rinse them through a sieve for accuracy. The biggest, tallest, fastest, richest so often turns out to be the second biggest, second tallest, second fastest, and nowhere near the richest.

-

Cut the fat, check the figures

Simply shedding fat does wonders for sentences. Down with bloat.

“The test of style is economy of the reader’s attention” (Herbert Spencer).

“If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out” (George Orwell).

“Murder your darlings” (Arthur Quiller- Couch).

“Read over your compositions, and wherever you meet with a passage which you think is particularly fine, strike it out” (Samuel Johnson).

It would spare editors the tedium of nouns acting as magnets to every passing iron filing. Strunk’s words in Elements of Style should be chiseled in marble:

“Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should contain no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.”

-

Be positive

Sentences should assert. Express even a negative in a positive form. That sounds like boosterism, but it’s a risk worth taking since it is quicker and easier to understand what is than what is not.

Original:

The figures seem to us to provide no indication that costs and prices . . . would not have been lower if competition had not been restricted.

My edit:

The figures seem to us to provide no indication that competition would have produced higher costs and prices.

Original:

It is unlikely that contributions will not be raised.

My edit:

It is likely that contributions will be raised.

Original:

The project was not successful.

My edit:

The project failed.

Original:

They did not pay attention to the claim.

My edit:

They ignored the claim.

-

Put people first

Aim to make the sentences bear directly on the reader. People can recognize themselves in particulars. The abstract is another world. The writer must make it visible by concrete illustration. This means calling a spade a spade and not a factor of production. Eyes that glaze over at “a domestic accommodation energy- saving improvement program” will focus on “how to qualify for state money for insulating your house.”

Economic and political reports abound with abstractions that cry out for humanizing.

Do I Make Myself Clear by Sir Harold Evans is published by Hachette, price £20 (hardback).

Email pged@pressgazette.co.uk to point out mistakes, provide story tips or send in a letter for publication on our "Letters Page" blog